Scaling near to 1M TPS

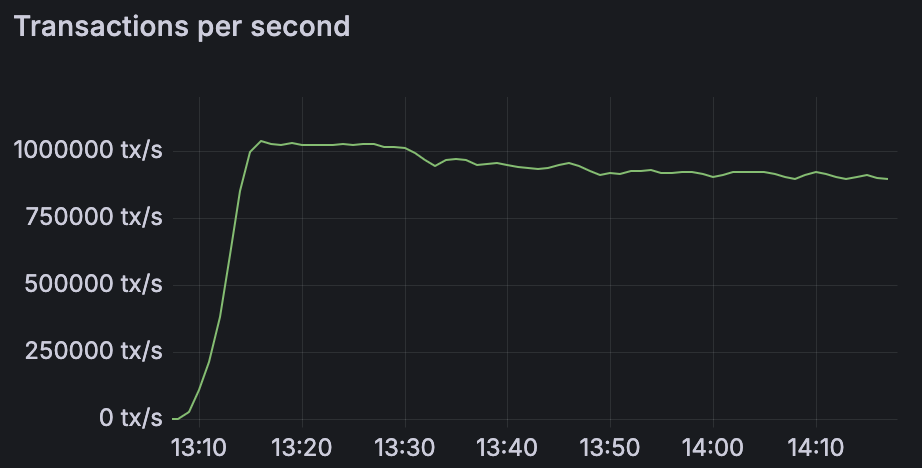

We achieved 1M TPS on NEAR after many optimizations targeted at increasing throughput and scaling up the number of shards, only using commodity hardware. Below is a detailed look at the techniques that made it possible.

Authors: Andrea Spurio, Jan Malinowski, Slava Savenko, Darioush Jalali

Background on NEAR protocol, stateless validation, and sharding

NEAR uses a sharded, leader-based blockchain where each block contains the outputs of multiple shards, and each shard processes a disjoint portion of the state. Blocks are produced in a fixed sequence of block producers, while chunk producers (one per shard per height) assemble the transactions and state transitions for their shard into “chunks.” A block is essentially a container for these chunks plus receipts that move between shards. Cross-shard communication is fully asynchronous: when a transaction in shard A produces a receipt for shard B, that receipt is routed via the next block and executed by shard B in its future chunk. This design avoids global synchronous execution and keeps the system horizontally scalable as shards are added.

To make such a sharded chain verifiable by ordinary nodes, NEAR supports stateless validation: instead of requiring validators to store the full state, each chunk includes Merkle proofs (state witnesses) that show which parts of the state were read or written. A validating node only needs to verify signatures, apply the transactions over the provided witness, and check that the resulting state root matches the one committed by the chunk producer. This allows NEAR to retain strong security even when individual validators are only assigned to a single shard at a time.

Goal, setup, and focus of benchmark

The focus of this benchmark is to demonstrate NEAR protocol’s scalability via sharding on commodity hardware. In this benchmark, we demonstrate this by using the same neard client reference implementation codebase that runs on mainnet (under different configuration and network setup), to run validator nodes of a high-throughput chain, reaching a peak of 1M native token transfers per second.

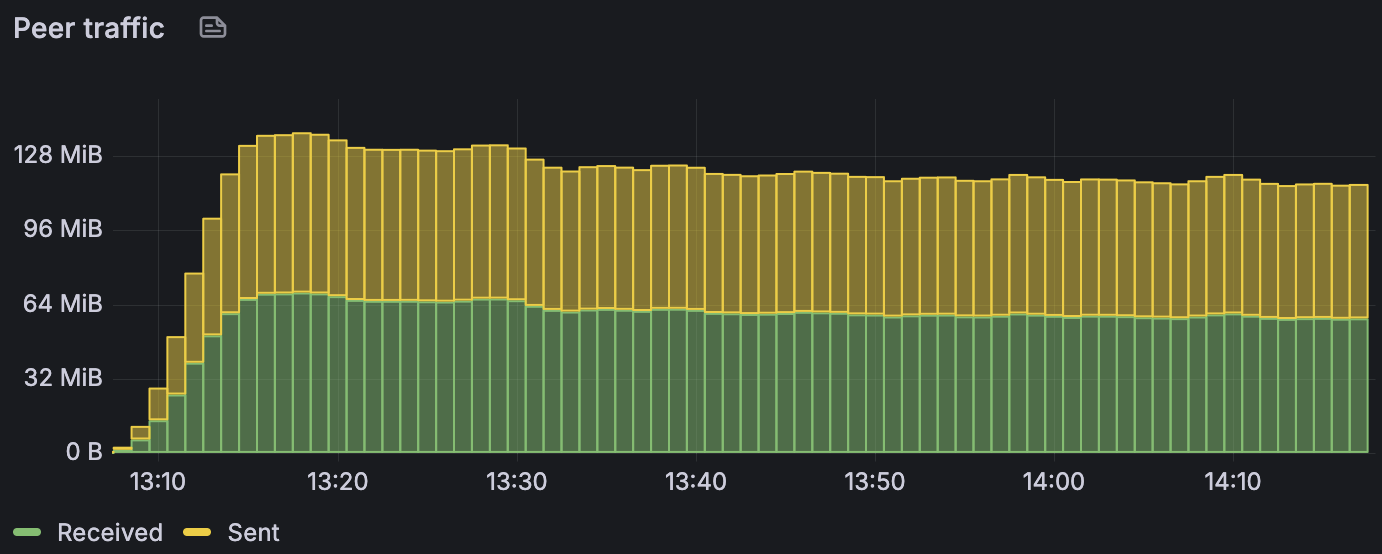

We considered cloud hardware that fits in a $1k / month budget for compute and storage. We believe this budget is not excessive in a way that is harmful to decentralization. Our estimates for network traffic at 64 MB/s is $4 / hr using on-demand cloud provider rates. Validators may run on dedicated hardware or use cloud provider service agreements to further reduce costs.

We were able to reach that target using 70 shards and the setup detailed below:

Configuration of network and nodes

- 140 nodes, assigned to 70 shards. Both nodes assigned to the same shard have the chunk producer role, i.e., alternate turns in producing chunks for their assigned shard.

- Nodes assigned across three regions:

- us-central1 - 47 nodes

- us-east1 - 47 nodes

- us-east4 - 46 nodes

- All nodes using:

- GCP c4d-highmem-16 (8-core CPUs)

- 200 GB hyperdisk-balanced (440 MB/s, 4200 IOPS) as a boot disk

- 400 GB hyperdisk-balanced (1200 MB/s, 20000 IOPS) as an attached disk

A note about “mandates” and network security in sharded stateless validation

In stateless validation, a block producer must include endorsement from a sufficient amount of stake (that have validated the state witness proving the new chunk is valid) in order to include a chunk in a block.

NEAR uses a concept called mandates, which represents a tradeoff between the number of witnesses each validator must validate and the safety of the network.

In this work, we choose a number of mandates such that the amount of witnesses validated by each node is the same as it is on the current top 20% mainnet network validators (by stake).

In other words, more nodes are needed to have acceptable security guarantees on a 70 shard network (this allows an increase in the number of mandates). Note that these additional nodes do not need to track state, therefore they need less powerful hardware compared to chunk producer nodes. Starting such large networks could easily have a justifiable cost to scale an actual blockchain, however the cost is prohibitive for benchmarking. Therefore, we study how the nodes of such a chain would operate under a computationally equivalent load that provides security for mainnet (each node ends up validating state witnesses for on average 5 shards).

We refer the reader to additional references around selecting secure committees:

- Sharding: How many shards are safe?

- Nearcore source code for mandate selection

- Random Sampling of NEAR’s Validators

Workload

- Native token transfers,

- Account selection:

- Source accounts are selected from the shard of the producer using the Zipf-Mandelbrot distribution.

- The target accounts pool is assembled using all accounts from all the shards randomly shuffled (on each load generator independently) to avoid shards skew. The Zipf-Mandelbrot distribution is afterwards used to select the target accounts for each particular transaction.

- Distribution parameters for the source and target accounts selection are: shift=2.7, exponent=1.0. For the 1M accounts in 70 shards with 2 producers per shard that results in the following probabilities:

- ~3.5% for the most frequent source account on each load producer.

- ~2% for the most frequent target account on each load producer.

- Total number of accounts: 1M

Running the benchmark

To run the benchmark, first we create the accounts and access keys, and then gradually increase traffic over 6 minutes before applying the maximum load. During the initial period, we keep the traffic low as the chain initially has a few chunk/block misses while nodes are coming online.

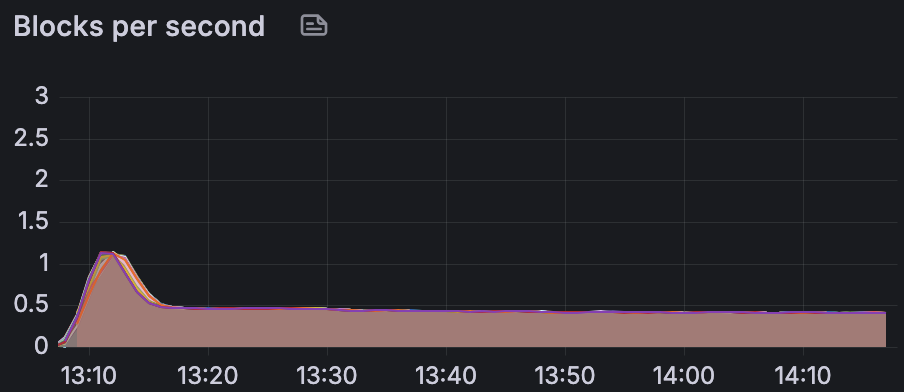

Chunk producer nodes generate and sign the transactions: this simplified our benchmarking setup and allowed us to exclude RPC and focus on validator throughput. In the steady state, we apply a constant load and the system operates at 0.5 block/s without chunk/block misses. Peer traffic reaches around 64 MB/s in send and receive.

|

|

|

Optimizations

The following is a list of the more impactful and large scale optimizations the team worked on. We also worked on many other smaller scale optimizations, which are not detailed here.

Early transaction preparation

In normal operation, the chunk producer starts ordering transactions from the pool when it’s time to produce the chunk. This allows for inclusion of transactions that were submitted up to that moment, however delaying preparation of transactions until the last moment adds to the overall block latency.

We implemented a change that prepares transactions as soon as the prior chunk’s post-state is computed, trading off inclusion of most recent transactions in favor of higher chain throughput. This behavior is controlled by the enable_early_prepare_transactions configuration option, and can be enabled on a per-chunk producer basis.

Persisting less to disk

In this benchmark, we focused on validator performance. By default, and out of convenience, neard persists a lot of data to RocksDB for each block. We found that large portions of this data was not needed for validators, and added configuration options to allow disabling writing of those (with sensible defaults – to avoid impacting existing node operator flows).

save_tx_outcomes: Transaction outcomes are used by RPC nodes to respond to status queries, but not needed for validators.save_state_changes: StateChanges column is used by RPC nodes to respond to queries and by the Rosetta indexer, but not needed for validators.save_untracked_partial_chunks_parts: PartialChunks are saved in order to answer requests from nodes that are catching up with the chain; disabling this option avoids writing PartialChunks in the database, and keeps them only in the memory cache.

Ed25519 batch signature verification

NEAR blockchain natively supports ED25519 and SECP256K1 signatures. Since mostly ED25519 signatures are used, we implemented an optimization to verify those signatures in batches of 128, with graceful fallback to verifying individual signatures.

Batched signature verification uses around 40% less cpu resources. However this translated to only around 7-10% improvement in the overall benchmark.

Deserialized column cache

We found the NEAR implementation performs frequent reads of data such as recent chunks, blocks, and block headers. This would not only read through RocksDB but would also deserialize the item on each access! To mitigate this, we implemented a column-level cache for some of these frequently referenced columns, based on profiling observations.

RocksDB Tuning

To improve database throughput under write-heavy workloads, we implemented the following RocksDB optimizations:

- Pipelined Writes: enabled pipelined write path to reduce write stall latency, allowing write operations to overlap more efficiently.

- WAL Tuning: configured WAL (Write-Ahead Log) to sync roughly every 1 MiB, smoothing I/O patterns and reducing latency spikes from large fsync bursts.

- Compaction Tuning: relaxed L0 compaction triggers so background compaction interferes less with foreground writes, and increased target file sizes to reduce the number of SST files. Added compaction read-ahead to help sequential reads during compaction.

- Memtable Configuration: increased memtable memory budget and write buffer count to absorb write bursts and reduce flush frequency.

- Column Family Tuning: allocated more resources to write-heavy column families with larger memory budgets, more sub-compaction jobs for parallelism and bigger write buffers.

TCP Tuning

To reduce latency in state witness distribution and chunk distribution, we implemented several Linux TCP stack optimizations:

- BBR Congestion Control: we switched to Google’s BBR algorithm paired with Fair Queueing (fq). BBR models network capacity based on bandwidth and round-trip time rather than packet loss, achieving higher throughput and lower latency.

- Path MTU Discovery: enabled to automatically discover the optimal MTU along network paths, preventing packet fragmentation and reducing overhead.

- Connection Handling: Increased the SYN backlog to 8096 to queue more incoming connection requests during traffic bursts.

- Buffer Tuning: for benchmarks, we significantly increased socket buffer sizes and raised the network device backlog, allowing the kernel to handle high-volume data transfers without dropping packets.

Actor separation

neard is implemented using an actor-style programming: a collection of independent actors, each with its own state and a mailbox for incoming messages. Actors communicate exclusively by sending asynchronous messages. However, in practice individual actors can become bottlenecks, for example:

- some actors cannot make progress while waiting for a response from another actor,

- an actor takes on too many responsibilities, and ends up handling large amounts of work on the critical path.

Some examples where we identified and solved this type of issue:

- Creating state witnesses on a thread pool to avoid blocking a critical actor

- Separate actor for state witnesses

- Moving chunk-endorsement processing to a multi-threaded actor

Lock contention & trie witness recording optimizations

- Avoiding serialization and hashing nodes when not needed,

- Using dashmap to reduce lock contention in recorder,

- Removed unnecessary tracking of “visited nodes” for state witness – this was taking place due to re-using code from “state sync part verification” logic.

Solutions for some problems we encountered

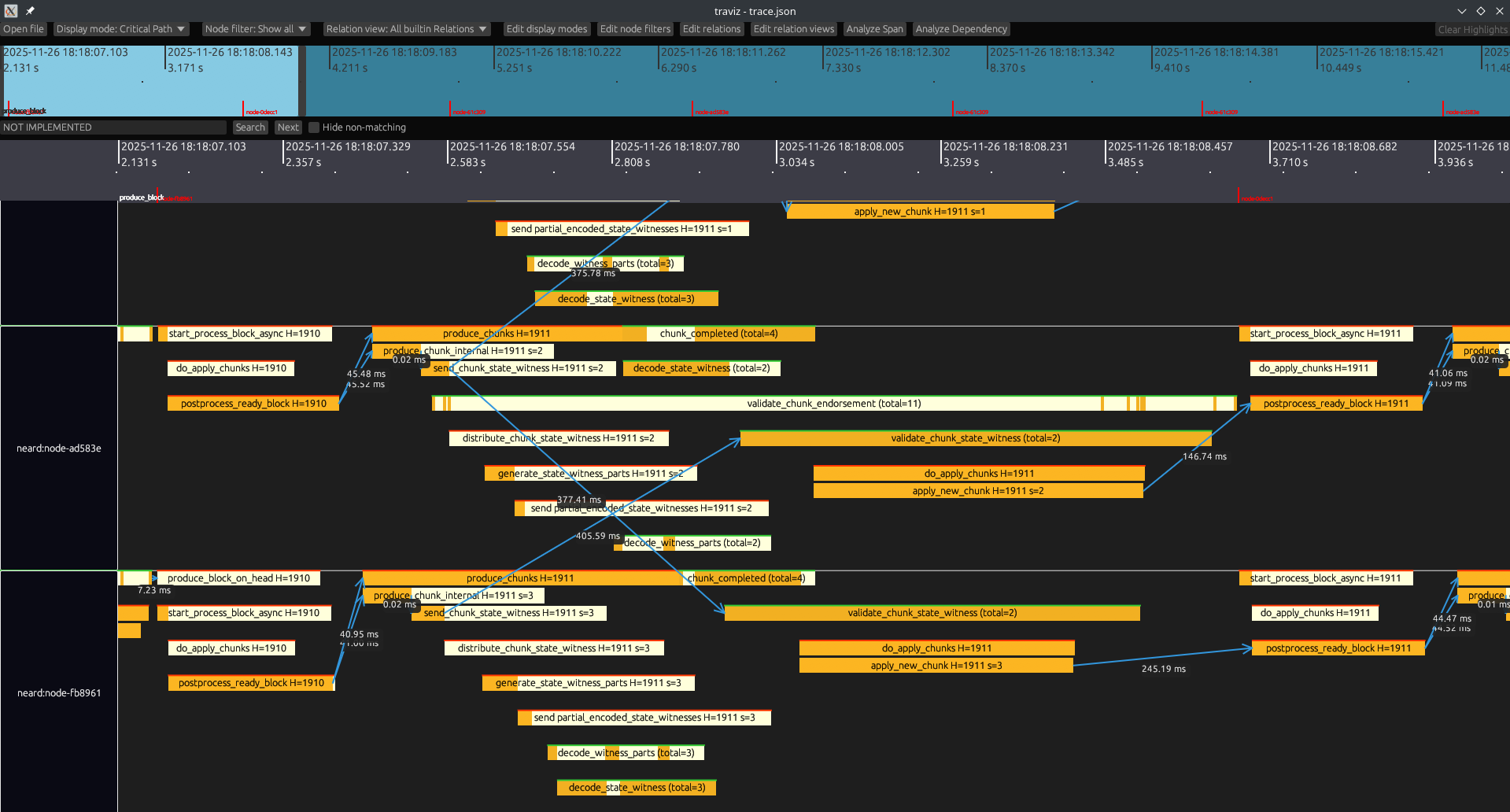

Visualizing OpenTelemetry traces: Traviz

We used OpenTelemetry traces to analyze node performance. The traces allow us to view exactly how the node operates - when it receives and sends data, when it computes things, and how different nodes relate to each other. Being able to visually analyze all operations in the network was invaluable in understanding what the critical path looks like and which optimizations can be implemented to improve performance.

neard exports tracing data in an OpenTelemetry compatible format. A few mature tools such as Tempo and Jaeger are available in this domain, however they mostly focus on a hierarchical structure for traces (e.g., to break down calls to micro services).

This was not enough to help us figure out bottlenecks in a distributed system such as a multi-shard blockchain network. Because of that we developed an in-house trace visualization tool - Traviz. It allows us to view the data exactly the way we need, and has custom NEAR-specific features which make analyzing the NEAR flow easier. We’re planning to publish another blog post with more details about traviz.

Consistently measuring benchmark results and monitoring regressions

To find out the maximum throughput the chain can support we have disabled/adjusted some safeguards supporting the chain stability in the prod. Those include the compute-cost and witness size caps for example that are used to limit the chunk size. While doing so we were not sure precisely which way the chain would break under the traffic exceeding its capacity. It turns out the chain reacts by exponentially increasing the block time and chunk size leading to missing blocks and severe drop in performance. Initial measurements involved running the series of experiments with the varying load to find out the optimal TPS volume. That was extremely human- and hardware- resources consuming, and resulted in noisy (+- 10%) measurements at irregular occasions. Finding the source of regressions (that did happen) used to be a rather painful procedure.

To improve the situation we implemented a proportional–integral–derivative controller (with some fine-tuning to better represent the system’s response) that modifies the load TPS to target the desired block rate. Experiments are fully reproducible with very low variance, allowing to catch the deviations of ~1%. That allowed us to fully automate the benchmarks and add them as periodic CI jobs, with the perf measurements and telemetry saved as artifacts for each run.

For the continuous benchmarking we are targeting the block production time of 1.5s. We found that it represents the throughput close to its maximum values while still keeping the chain in the stable operational range. The nightly jobs are run using the 4-shards chain as a minimal representative sample, and we are running the more expensive 20-shards scenario weekly. The CI setup also provides a convenient way to run the reproducible, self-documenting experiments with a few mouse clicks.

This proved to be useful not only for experiments run by the performance optimization team but also allowed us to catch and quickly bisect several performance regressions introduced by the others.

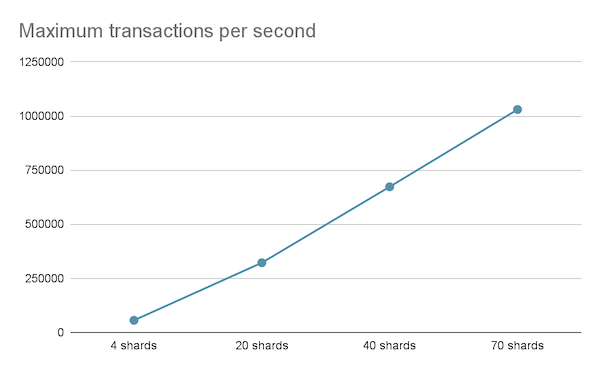

Scalability

Additionally, we report the following throughput capacity for smaller shards, keeping the same number of total accounts. Currently, mainnet is operating with 9 shards, and these experiments provide an idea about the shorter term scaling potential of the NEAR network:

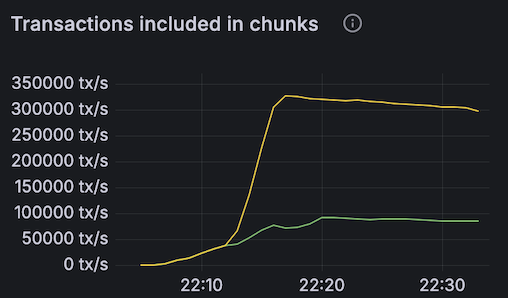

Impact of optimizations

To specifically highlight the impact of the optimizations, we compared the throughput of 4-shard and 20-shard networks, prior to the optimization work using a commit from master on Mar 25, 2025. The results show around 3.5x improvement (graph included for 20-shard comparison).

Reproducibility

To ensure the community and industry can verify these results, we are releasing the following deliverables:

- Open-source benchmark scripts

- Public Grafana dashboards with 1M TPS runs: Run 1, Run 2, Run 3

- Commit hash of the benchmarked code

These materials enable researchers, auditors, validators, and the wider blockchain ecosystem to reproduce the benchmark and validate these performance claims.

Future work

Optimistic execution and separating consensus from execution

Many parts of the code could be optimized with optimistic execution. Currently execution and consensus are interleaved - the network processes some data, then runs consensus to agree on the state and then processes some more data. It’d be more efficient to run execution in parallel with consensus instead of running them sequentially. This can be achieved using “optimistic” execution which runs on unconfirmed state before the consensus agrees on it.

Separating consensus and execution is the leading theme in the upcoming SPICE upgrade. In SPICE chunks will be produced without waiting for the previous ones to execute, allowing consensus and execution to run at the same time and improving performance. Some optimistic execution might still be needed to achieve maximum possible throughput.

Further reducing storage redundancies

neard still stores state in formats that have redundancies. For example, the State column stores reference counted trie nodes in by hash, and the reference count changes are stored in a separate column (TrieChanges), to enable garbage collection.

Since the time that stateless validation was introduced, most validators operate using in-memory state. RPC nodes still rely on the State column for responding to queries. In the future, RPC nodes may be sharded and also use in-memory state, which could allow further optimizations.

Benchmarking fungible token transfers

In this benchmark, we focused on native token transfers to focus on scalability of the chain independent of the contract runtime. Benchmarking fungible token transfers and optimizing the contract runtime remains as future work.

Benchmarking simplifications

This benchmark focuses on showing NEAR protocol’s scaling potential and providing a validator implementation backed by the same reference client protocol that runs NEAR mainnet today. We want to highlight areas we considered out of scope.

Further work is required to improve the following areas necessary to operate an entire blockchain ecosystem at levels of throughput similar to those demonstrated in this work:

- RPC & archival support: Nodes that operate as “RPC nodes”, with the purpose of responding to queries about blocks and state, persist more data to disk than is needed for validators to operate. Archival nodes persist even more data to disk, including all historical state and block information.

- State sync part generation: Currently in the NEAR protocol, validators divide the state into “parts” and persist parts to disk at the beginning of an epoch. These parts are then served to new nodes who join the network later. We exclude the creation of these parts from the benchmark. In a high throughput chain, theoretically storing these parts could be a specialized role.

- Gas limits and congestion control: Normally, gas limits are set based on usage of mainnet. High-throughput benchmarks involve chunk sizes significantly larger than those observed on mainnet, which impacts gas limits and congestion control. These parameters should be adjusted alongside actual network usage growth.

- Partial Chunk persistence: When the option

save_untracked_partial_chunks_partsis set to false, nodes will persist chunk parts only for the shard they track. All other part-owner nodes (the subset of nodes responsible for providing chunk availability guarantees) will only store partial chunks in a configurable-length in-memory cache. The downside of this configuration is that a node needing to request a chunk may not find any suitable peer able to respond successfully. This can happen if the chunk is too old thus out of the cache horizon, or if the other peer was restarted recently and its in-memory cache is fresh. A node that cannot fetch a required chunk will be unable to catch up to the latest block. This is not an issue in the benchmark because nodes are not restarted and no node is lagging behind the tip of the chain. - Data center location: In this benchmark, we placed nodes across three data centers in “us-central” and “us-east”. Further distributing nodes geographically improves decentralization, however it may impact the network throughput as a result of increased networking latency.